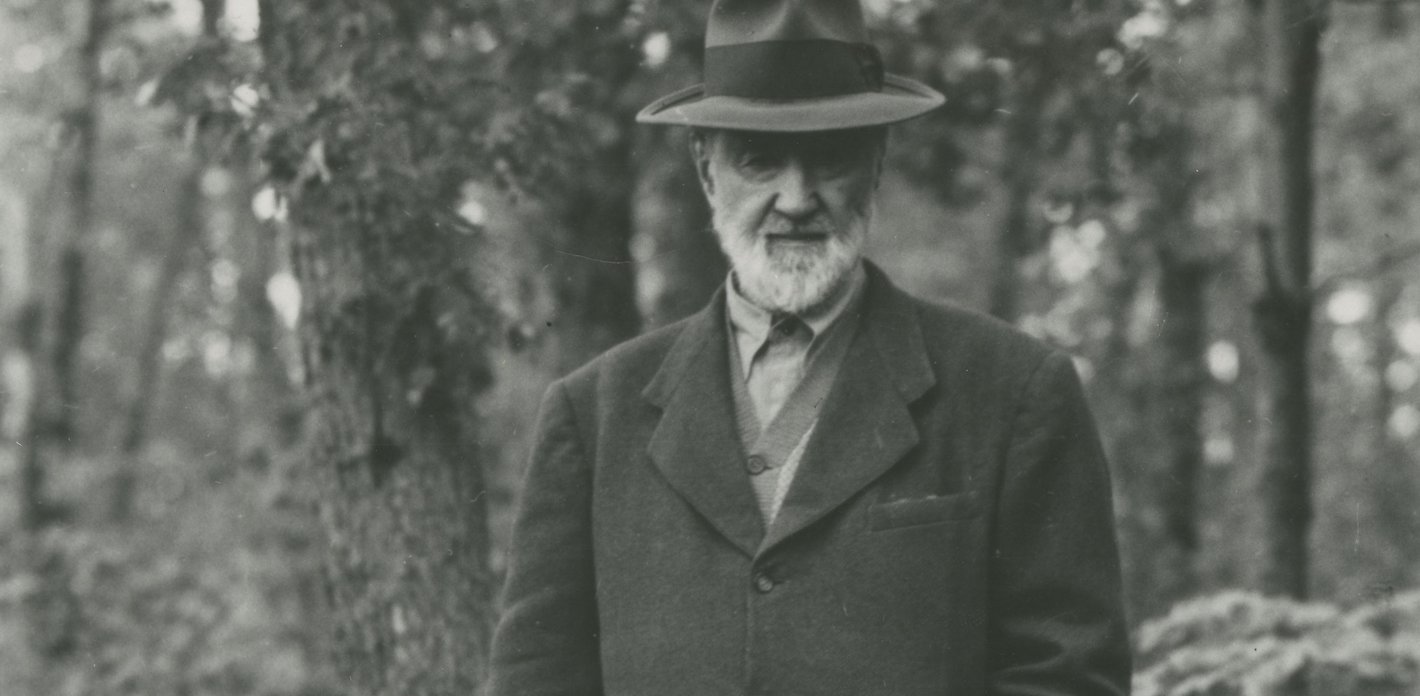

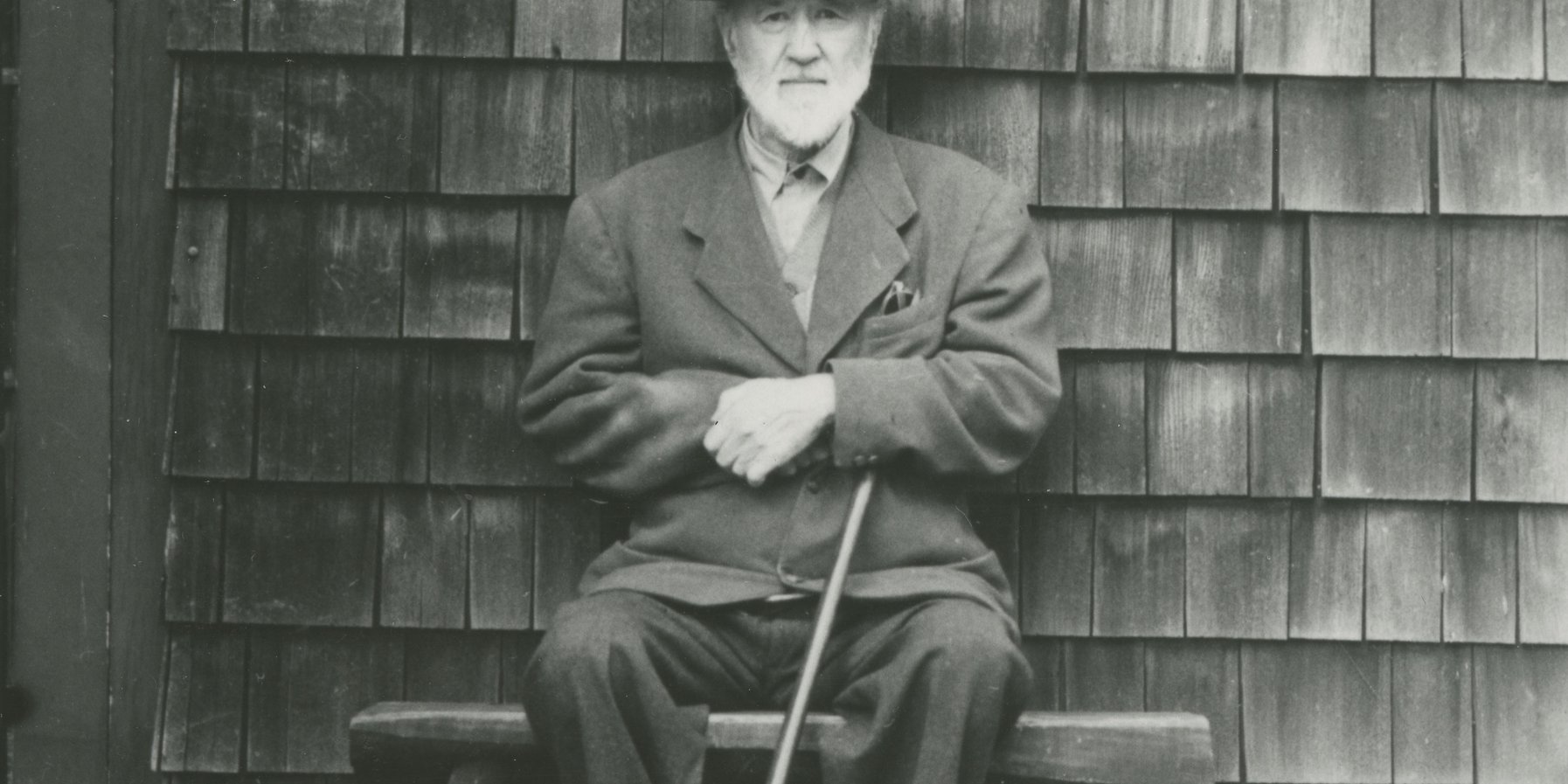

Dictionaries of music are fond of referring to Charles Ives as »a special case in music history« – and that's a pretty apt description: few other composers were so original and uncompromising, so free from the constraints of tradition and convention. The American composer, who was born in 1874, could afford this artistic freedom as music remained a lifelong sideline for him: Ives earnt his living as an insurance broker, a business that he was very successful at.

For all this, Ives produced an impressive body of music. In addition to four large-scale symphonies and other orchestral works (among them the famous piece »The Unanswered Question«), he wrote countless songs with piano accompaniment, two string quartets, several a cappella choruses and other chamber works. Ives also wrote a variety of essays on musical, political and philosophical subjects as well as explanatory texts to accompany individual compositions. His fascinating chamber music often surprises with unusual and challenging instrument combinations – perhaps one reason why it appears far too rarely on programmes.

Carles Ives: The Unanswered Question

Visions and Experiments

But Ives wasn't bothered by such practical considerations. His sole focus was the realisation of his artistic visions. And to implement these, no musical experiment was too much for him. Thus at the turn of the century he already anticipated many of the supposed revolutionary achievements of the (European) avant-garde in the 1950s, among them polyrhythmic writing, atonality and serial music, that is, composing according to strict mathematical rules. At the same time, Ives’s music oscillated between a simplicity redolent of folk songs and complex dissonance.

»Why tonality as such should be thrown out for good I can't see. Why it should always be present I can't see.«

Charles Ives

However, it was the musical collage that emerged as his most prominent composition technique. He loved integrating light music such as popular hits, gospel songs and marches into his works, and in his early compositions in particular, he tried to achieve a hyperrealistic reproduction of everyday sounds such as bells and sirens. His music also features numerous quotations from other composers' works of different eras.

Ives's use of light music in his scores prompted critics to compare him on more than one occasion with Gustav Mahler, who likewise incorporated functional and folk music into his works. But there is one decisive difference between the two composers: Mahler blended the different spheres into a new whole, whereas Ives let them stand unconnected, sometimes clearly contradicting one another.

The Utopia of Freedom: Ives and Transcendentalism

With this pluralistic approach, Ives was emulating his ideal of American transcendentalism, creating a musical reflection of the utopia of a society free of constraints.

The transcendentalists advocated a liberal lifestyle in which people took responsibility for themselves and lived at one with nature, and their philosophy plays a central role in Ives's »Concord Sonata«. The title refers to the small town of Concord in Massachusetts, which some see as America's Weimar. In the mid-19th century, philosophers and men of letters who criticised aspects of the society of the time, attacking the failings of American politics, religion and society in general and seeking for alternative ways of life, congregated here. It comes as no surprise that Charles Ives, who ignored conventions himself, felt attracted to the transcendentalist movement.

Text: Simon Chlosta