Text: Martin Greve, 31.08.2023

At the beginning of the twentieth century, some travellers would carry phonographs with them on their journey to record voices and songs on wax cylinders. In 1902, the Austrian archaeologist and anthropologist Felix von Luschan took such a device with him on an excavation near the Turkish city of Gaziantep, and recorded Turkish and Kurdish songs there. Similarly, Gustav Klameth, a theology student from Bohemia, recorded an Assyrian priest from Mardin (in what is today southern Turkey) singing three Kurdish songs on a phonograph in Jerusalem on New Year’s Eve of 1912.

These two audio documents are, as far as we know, the oldest recordings of Kurdish songs – chance discoveries that only survived in the phonogram archives of Vienna and Berlin by luck. A century later, the musicians of the Viennese group Danûk happened upon them and began preparing new arrangements of these old songs from the border region between Syria and Turkey, from which the group’s members were themselves forced to flee during the Syrian war.

Kurdistan Festival :17 – 19 November 2023

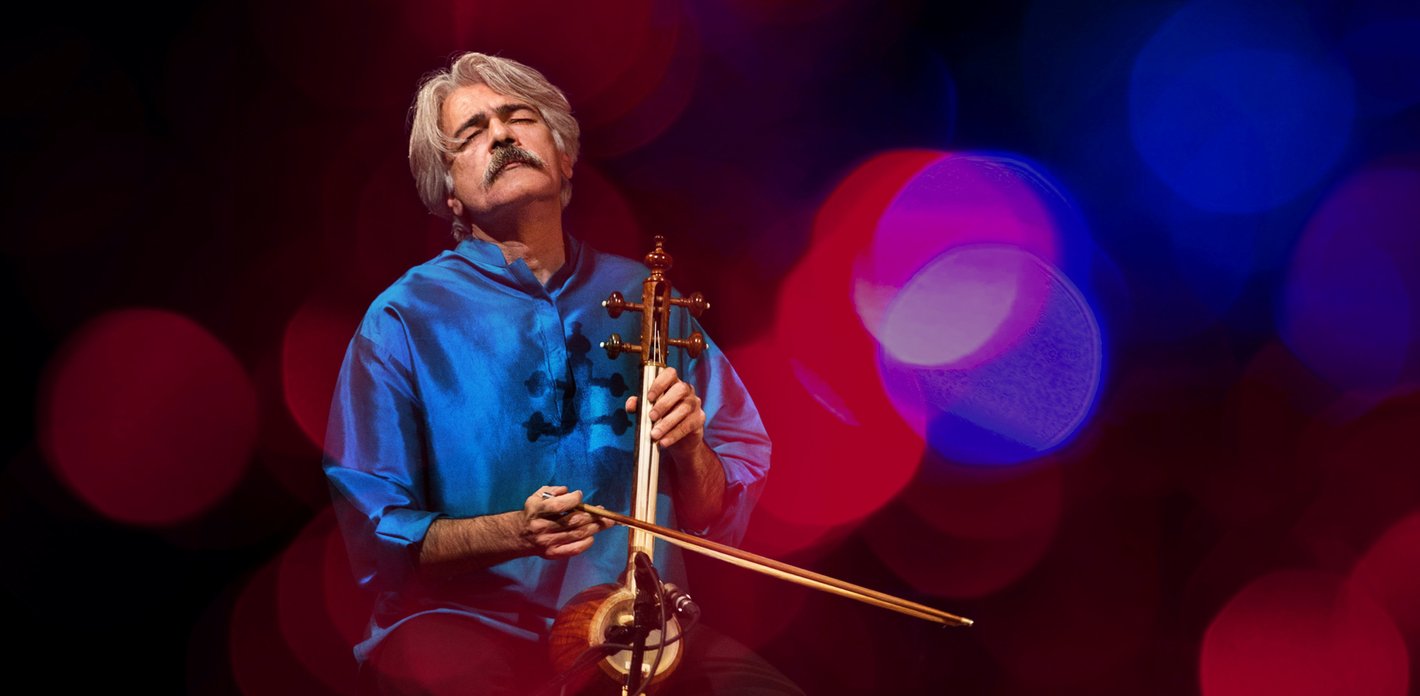

For one whole weekend, the Elbphilharmonie is celebrating the diversity and vitality of Kurdish music, with artists such as the singer Aynur and the kamancheh virtuoso Kayhan Kalhor.

Unforgotten

Today, Kurdish musicians are searching for old recordings in an effort to revive forgotten traditions. The most important source in that endeavour is not phonograph cylinders, however, but old music cassettes. Because since the introduction of cheap, transportable cassette recorders in the 1960s, local collectors everywhere began recording stories and songs that were passed down orally to preserve them for eternity. In 1991, the Istanbul-based label Kalan Müzik launched its archive series, and the Mahoor Institute in Tehran also released numerous recordings of Iranian-Kurdish music.

The region of Dersim

Over many decades, the brothers Metin and Kemal Kahraman, who originally gained fame in Turkey for their political songs, collected and performed the songs sung by the older generation in their home region of Dersim, a politically fraught area that lies in eastern Anatolia. In doing so, they triggered a major Dersim revival that led to the emergence of numerous other musicians in the scene. Take Maviş Güneşer, for example, who is not actually from the region, but who sang in the Kahramans’s ensemble and who has now reconstructed historic dirges about the massacres and battles of Dersim in 1937/1938. Or Aynur, the great Kurdish singer from southern Dersim. And, of course, Ahmet Aslan, who has long been a superstar in Turkey. Aslan’s vocal technique is unique: he ends most musical phrases with a kind of sigh that is not so much a traditional singing technique from Dersim but rather a reflection of the advanced age of the singers recorded by collectors. In Ahmet Aslan’s songs, that becomes an artistic embellishment.

What is Kurdistan?

The name Kurdistan is a dream, a hope, an illusion. For others it is also a nightmare, a justification for war and terror – the desire for another national state in a region in which so many others have brought disaster with ethnic cleansing and discrimination.

Kurdistan (the »Land of the Kurds«) has been used as a geographical name for centuries, but there has never been a Kurdish national state. However, provinces bearing this name did exist in the Ottoman Empire, and in Iran in 1946 – the short-lived, Soviet-supported Republic of Kurdistan (or the Republic of Mahabad) in the north-western corner of Persia. There have also been a few Kurdish regions that have achieved independence, for example the autonomous Kurdistan Region, which was realised in 1992 when the United Nations established a no-fly zone in northern Iraq; and Rojava in northern Syria, a de facto autonomous region formed in 2013 within the context of the Syrian civil war, but which – since the end of the so-called Islamic state – is coming under pressure from the central Syrian government in the south and Turkey in the north.

And a Kurdish state would not be particularly homogenous in any case – politically, linguistically, religiously, culturally or musically. There have always been sharp distinctions between the Ottoman or urban population on the one hand and the rural population on the other, between tribal and non-tribal Kurds. Furthermore, it’s not just Kurds living in the region: there are also large numbers of Turks, Turkmens, Arabs, Assyrians and Chaldeans. Until the genocide of the Armenians in 1915 – in which numerous Kurds also took part – they were the biggest minority.

In many languages

Kurdish languages belong to the Indo-European family of languages and, within that, to the Iranian group of languages. Kurdish is therefore not related to Arabic or Turkish, but to Persian. The most important Kurdish dialects are Kurmanji in the north and Sorani in the south. The case of Zaza shows how complex the relationship between linguistic and ethnic categories can be: in purely linguistic terms, Zaza apparently does not belong to the family of Kurdish languages, and is actually related to the Northwestern Iranian language Gorani. However, many of the two million Zaza speakers in eastern Anatolia identify as Kurdish – while others do not.

The Kurdish diaspora

Today, it is estimated that there are around 35 million Kurds, with around half of those in Turkey, six million each in Iraq and Iran, and more than two million in Syria and in Lebanon. But are these numbers still correct? Is it not the case that many more Kurds have been living outside of »Kurdistan« for a long time? Twentieth-century Kurdish history is marked by violence – from various brutally supressed uprisings in Turkey and the 40-year armed conflict between the Turkish army and the PKK with 40,000 dead, to the Iraqi regime’s poison gas attack on the Kurdish-Iraqi city of Halabja in 1988 with between 3,000 and 5,000 dead. Most recently, between 2014 and 2017, the so-called Islamic State massacred thousands of Kurdish Yazidis, and raped and abducted Yazidi women.

»Today, it is estimated that there are around 35 million Kurds.«

All the uprisings, wars and massacres, plus the economic hardship, drove more and more people from the mountains and villages into the region’s towns, and then onwards to distant cities such as Istanbul and Mosul. Many Kurdish villages are now deserted, especially in winter, with the former occupants and their descendants returning for visits only in summer. When European countries such as Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Sweden and the Netherlands began recruiting workers from Anatolia from 1961 onwards, and also began accepting larger numbers of political refugees, many Kurds saw an opportunity for a new life.

Across Europe, a dense network developed of Kurdish organisations, associations, cultural centres, women’s groups, childcare centres and parents’ associations. Major concerts and festivals featuring Kurdish singers are now held regularly, with these also attracting people from all backgrounds. The Ahmet Kaya Kurdish Cultural Centre in Paris, which was named after the famous Turkish-Kurdish singer who died in exile in Paris in 2000, was the scene of a tragic attack last December, when a right-wing extremist killed three people, among them the Kurdish singer Mîr Perwer.

Diverse musical traditions

A large majority of Kurds are Sunni Muslims, and all the familiar Islamic forms of singing such as the call to prayer, reading from the Koran and various hymns are also common among Kurdish groups, as are the traditions of some Sufi orders, in particular the Qadiriyya and the Naqshbandi.

In the cult of the Ahl-e Haqq in southern Iran, a small long-necked lute called tembûr is played in accompaniment to sacred songs (kalām). In the religious gatherings, the faithful sing nazm, a metrically free call and response between the singer and the congregation, or as a choir, and this is sometimes accompanied with hand-clapping. Both the playing technique for the tembûr and the vocal technique resemble Persian art music.

Tembûr-Solo (Ahl-e Haqq)

With the Yazidis in northern Iraq, Turkey and Armenia, the caste of the qawāl is responsible for the recitation and singing of religious hymns (qawl). As a pair of instruments, the šabbāba (end-blown flute) and daff (frame drum with cymbals) are revered as particularly holy, and may only be played by a qawāl. A minority of the Kurmanji- and Zaza-speaking population in Turkey belong to the Alevi tradition. Historically, the long-necked lute tomir played an important part in their religious gatherings, but today the modern Turkish bağlama lute is almost always used. The region of Dersim far in the northwest of traditional Kurdistan, with its majority population of Zaza-speaking Alevites, plays a special role here.

Today, this Dersim Alevism is largely fused with Anatolian Alevism, but it bore distinct characteristics into the late 20th century. In their ceremonies, spiritual leaders (dedes) would sing a rich repertoire that moved Dersim’s faithful to tears and put them in a trance. However, Dersim’s most important literary and musical tradition is the singing of dirges, which are performed alone or accompanied by individual instruments such as the small lute tomir or the European violin. Most of the songs that have been preserved are about the massacres perpetrated on the people of Dersim by the Turkish army in 1937–38. By now, however, most musicians have switched from the small tomir to the larger bağlama; among them is Erdal Erzincan, who is regarded as the absolute master of the instrument.

Kurdish music on Soviet radio

Surprisingly, it was the Soviet-Armenian radio station Eriwan that first began broadcasting regularly in Kurdish in the 1930s. The short-wave channel could be received far beyond Armenia’s borders – in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran and in several Soviet republics. Over many decades and across national borders, this allowed Kurds to get to know poet-singers (dengbêj) from various Kurdish regions for the first time, among them great names such as Şakiro, Reso and Karapetê Xaco.

Later, during the 1950s and 1960s, Kurdish-language broadcasts were also made from Tehran and Baghdad, and a number of new Kurdish singers gained prominence, for example Mihemed Arif Cizrawî and his brother Hesen Cizrawî, Mêryem Xan, Aram Tigran and Ayşe Xan. In contrast, Kurdish remained controversial in Turkey for a long time. It wasn’t until 2004 that the first state Kurdish TV channel – TRT Kurdî – began broadcasting there. For musicians in Turkey, describing oneself as Kurdish was still a risky move.

Some Kurdish singers such as Diyarbakırlı Celâl Gülses, and later İbrahim Tatlıses, did become popular across Turkey, but they did so singing Turkish-language songs. Only in the late 1970s did the first Kurdish singers from Turkey – figures such as Şivan Perwer and later Nizamettin Arıç – really emerge. After 1991, when the ban on the Kurdish language in Turkey was lifted, Istanbul finally became a centre of Kurdish music production. Kurdish music gradually lost its political baggage, and musicians singing in Kurdish such as Aynur and the group Kardeş Türküler became popular across Turkey and beyond. These groups kept introducing new instruments such as the electric bağlama, international percussion

Live stream: Aynur at the Elbphilharmonie (March 2022)

New connections :The artists at the »Kurdistan Festival«

Apart from a few exceptions, none of the musicians performing at the Elbphilharmonie’s »Kurdistan Festival« live in the Kurdish region. The band Kurdophone is based in Vienna, and Danûk is active across the whole of Europe. Aynur settled in Amsterdam, Astare Artner in Cologne and Ahmet Aslan in Istanbul, while Kayhan Kalhor has now returned to Iran after many years living in the USA.

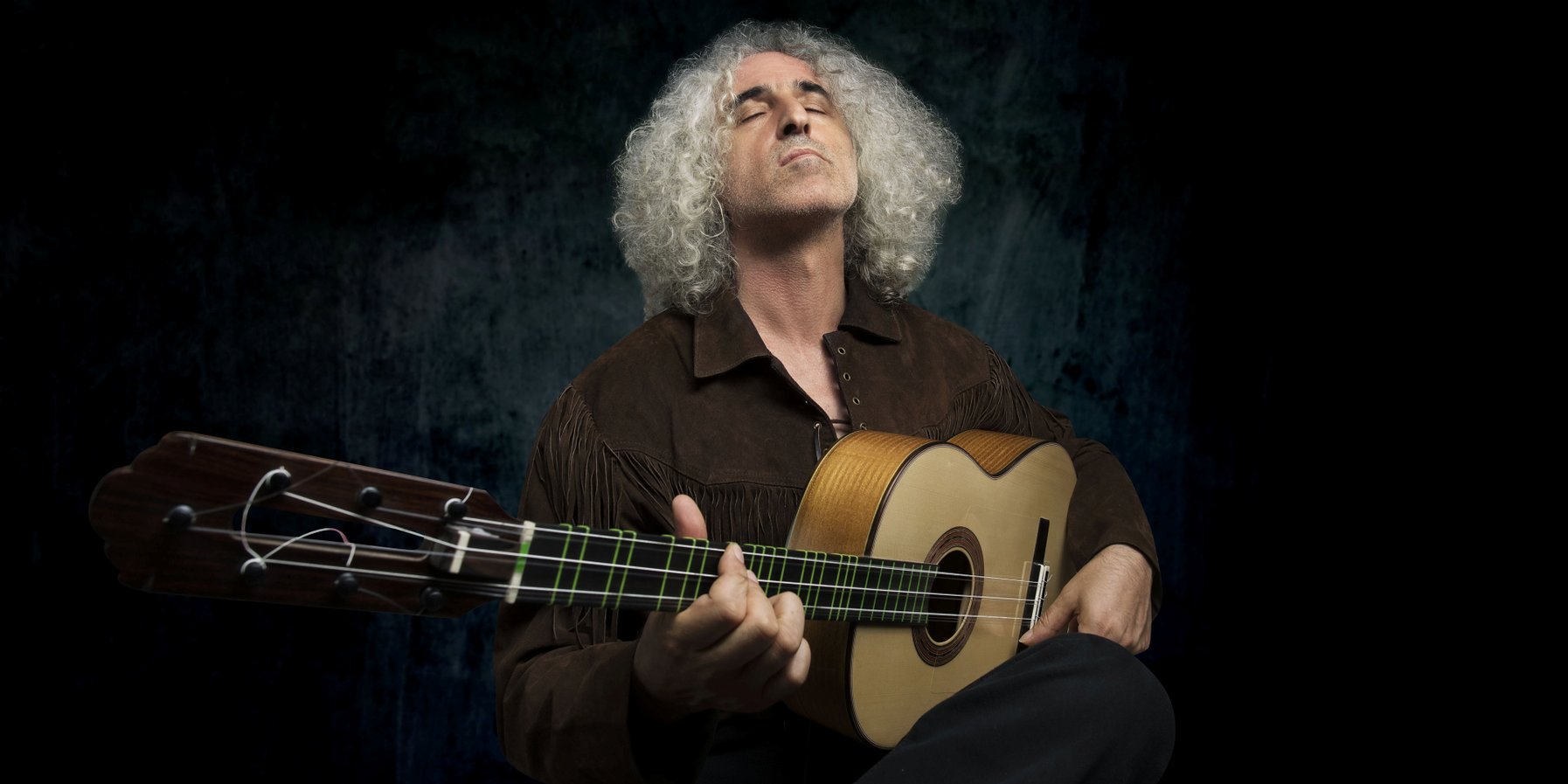

In Europe, many of these Kurdish musicians seek to integrate jazz, flamenco, rock, western classical music or contemporary New Music into their work. Kurdophone, for example, is a collective of Iranian-Kurdish and Austrian musicians. Taner Akyol, who comes from Dersim, composed a piece for chamber orchestra (»Tertele«) that was premiered in the Elbphilharmonie in 2018. Ahmet Aslan, who is also from Dersim, learned the flamenco guitar while studying at the Codarts World Music Academy in Rotterdam. The arrangements for Aynur’s album »Hevra/Together« (2014) are by the Spanish musician Javier Linón. And the singer now also works with western classical musicians and recently partnered with the NDR Bigband in Hamburg.

Others, like Danûk, seek out old recordings in an effort to breathe new life into forgotten songs. Take Ali Doğan Gönültaş, for example, who comes from Kiğı, a remote small town that was once an Armenian bishop’s see, was later forgotten and eventually became a no-go area at the centre of battles between the Turkish army and the PKK. Gönültaş was probably the first to search for forgotten songs there and to put his own stamp on them. However, new combinations of old traditions are also being attempted in Europe, for example in Gönültaş’s musical encounter with the poet-singer Saîdê Goyî from the province of Sirnak, 450 kilometres away in the Turkish-Iraqi border region. Or, at the festival, in the musical meeting of the Armenian duduk player Vardan Hovanissian and the Dersim singer and saz virtuoso Emre Gültekin.

And finally in the great summit meeting of this festival: when the bağlama virtuoso Erdal Erzincan from the eastern Anatolian city of Erzurum meets the Kurdish-Iranian kamancheh player Kayhan Kalhor. On the following day, Kalhor will be joining the singer Aynur and Hamburg’s Ensemble Resonanz: his composition »Silent City« is dedicated to the city of Halabja, which was almost completely destroyed by the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in 1988.

This article was first published in Elbphilharmonie Magazine (Issue 3/23).

Übersetzung: Seiriol Dafydd

Kurdistan Festival :The concerts

- Elbphilharmonie Kleiner Saal

»Kurdistan« Festival

Past Concert - Elbphilharmonie Großer Saal

Aynur / Kayhan Kalhor / Ensemble Resonanz

»Kurdistan« Festival

LivestreamPast Concert - Elbphilharmonie Kleiner Saal

Homage to forgotten Kurdish songs – Festival »Kurdistan« / World Classical Music

Past Concert - Elbphilharmonie Kleiner Saal

Kayhan Kalhor & Erdal Erzincan

»Kurdistan« Festival

Past Concert - Elbphilharmonie Kaistudio 1

Dengbêj & Stranbêj – the epic song of Kurdistan

Festival »Kurdistan«

Past Concert - Elbphilharmonie Kleiner Saal

Ali Doğan Gönültaş Trio / Maviş Güneşer Trio / Ahmet Aslan

Mythos Dersim – A Forum for Anatolian Culture / »Kurdistan« Festival

Past Concert - Elbphilharmonie Kaistudio 1

Lamentations, Tears and Miracles – Loss and Nostalgia in the Music of Dersim

Elbphilharmonie PLUS / Lecture / Festival »Kurdistan«

Past Event